“I remember every school morning reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, my eyes upon the stars and stripes of the flag, but at the same time I could see from the window the barbed wire and the sentry towers where guards kept guns trained on us… I remember a terrifying moment while I was held there when armed military police burst into the barracks and hauled away several young men… I finally saw where they had been taken: a concrete cellblock called the stockade… fading were brown splotches I was told were blood stains. This was what could happen in an America that had become un-American.” (Takei 2017)

George Takei is well-known and respected for his role on the show Star Trek, however, it is doubtful that many think of Takei when remembering Japanese internment camps during World War II. The quote above is from an Opinion article Takei wrote for the New York Times, comparing Japanese internment to the growing hostility in the United States towards Muslims. The description Takei provides is a stark one and it gives insight into the confusing life inside relocation camps. Many of the interned were born in raised in America, and after being forced to relocate, their view of what being an “American” meant was completely shattered. The forced relocation of Japanese Americans residing on the West Coast during WWII also caused an identity crisis for many, there was a terrific pull between celebrating both their Japanese and American culture and heritage and the extreme hatred and disgust towards the Japanese that was circulating through the United States during the time.

In February of 1942, ten weeks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed the Executive Order 9066. The order stated that government could remove people who posed threats from any military area, in 1942 it was determined that Japanese or Japanese American citizens living on the West Coast posed the biggest threat to the United States. “Following Pearl Harbor, the US incarcerated nearly all Japanese Americans, including children, on the West Coast in internment camps for an average of 3.5 years.” (Saavedra 2015, 60) Had the attack on Pearl Harbor not occurred, Japanese-American citizens, mostly living on the West Coast, would not have been forced to relocate to camps. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, media started distinguishing Japanese people in the United States as the “other,” inherently different and dangerous, which is why this heightened paranoia seemed to take off within the United States. Perhaps, during wartime ethical considerations are less prominent and biases and resentment take the place of logic and reason.

“A rising crescendo of demands for removal of Japanese aliens from the Pacific seacoast reflects the strong feeling left by the Pearl Harbor tragedy… This feeling of uncertainty affects the status not only of Japanese aliens but Japanese of American birth and citizenship. The feeling does not extend to citizens of German or Italian parentage.” (Brink)

This excerpt above was taken from a newspaper article by Rodney Brink for the Christian Science Monitor. The passage shows how media helped guide and grow people’s fear towards the Japanese during WWII. Decisions based on race, assumption and fear seemed to govern the political decision to intern almost 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. (Fickle 2014, 741) In times of fear, like wartime, humans have a heightened sense of paranoia towards the “other.” The other is anything different, and that usually comes across most poignantly in racial or ethnic differences. Perhaps this feeling of the “other” made it so easy for the US to intern Japanese Americans, especially after their cruel attack on Pearl Harbor.

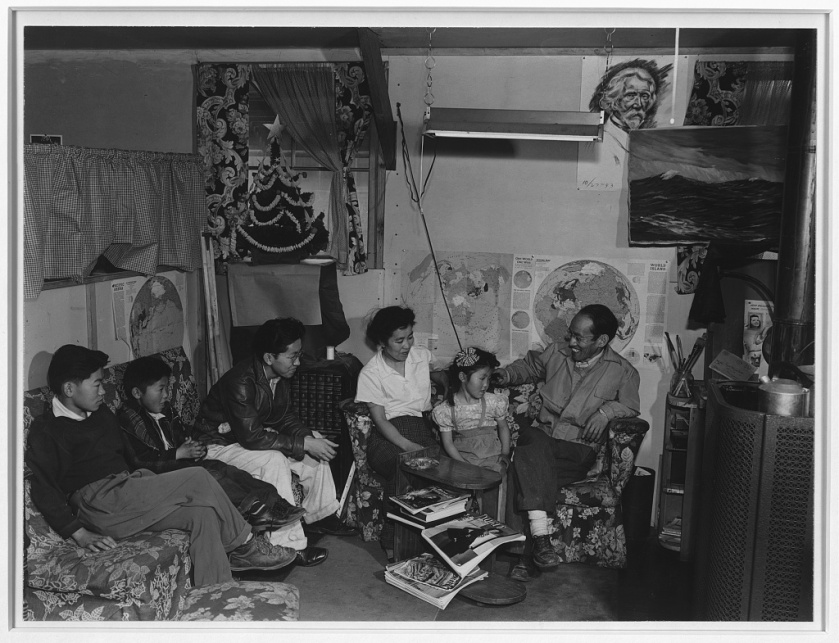

In the photo above, the Tojo Miatake family is photographed by Ansel Adams in a candid representation. It seems the family has done their best to make a life within the restraints of the “relocation” camp they were forced to move into. The walls lined with maps, and the small Christmas tree in the back shows the family was integrated into a classic American lifestyle. Even with the attempt at decor, there is a weight that the photograph carries. The boy closest to the camera appears cold and tense, almost as if while the rest of the family tries to adapt to this new normal, he can’t seem to forget the ugliness of the situation. The Western aspects of the whole documentation of Ansel Adam’s work at the Manzanar Relocation Center cannot be overlooked. These humans were just as ingrained in United States society as any other American, but their looks and their “otherness” made other US citizens view them as the enemy.

above, we see a similar scenario to the photo of the Tojo Miatake family. All three of the photos were taken by Ansel Adams as he documented life at the Manzanar Relocation Center. In the photo on the left, a Catholic church is pictured. The Japanese within the center would have built this church as a place of worship and to come together. The photo on the right shows to men at the center who worked for the co-op and who, on this day, were selling pies. These photos paint a picture of a group of people who were far less “other” than the media and government made them out to be. The idea of “otherness” was most certainly capitalized by displaying archaic stereotypes and beliefs through the propaganda that was distributed among United States citizens.

Propaganda issued by the United States government planted seeds of stereotypes within the minds of American citizens. When Japanese Americans were interned there was a growing sentiment among white US citizens that the Japanese were dangerous and untrustworthy. The resentment towards the Japanese after the attack on Pearl Harbor made it incredibly easy for the government to create a sense of paranoia among U.S. citizens. In both photos above, it appears as the people in these internment camps are far from the brutalizing savages that they were portrayed as by the government. In the photograph on the left, a Catholic Church is pictured… while in the picture on the right, three Japanese-American citizens present pies at a co-op store within the center. These portrayals are real, and quite different from the images planted into the minds of American people, the Japanese-Americans in these camps, for the most part, were integrated into American culture and practices of the time.

All of the photos above are demonstrations of United States government propaganda against the Japanese during World War II. The first and last image shown are both implicating that all Japanese Americans are spies, these images provoke a distrust of neighbors, co-workers, etc. The middle image is a diagram, using large numbers and facts to raise suspicion towards any Japanese or Japanese American. The last image is also particularly interesting as it portrays the Japanese figure as a rat with large ears. These pictures all show the hysteria that the US government and media were able to create by sensationalizing events and using fear tactics to turn US citizens against Japanese Americans. These images of propaganda are in stark contrast to the photographs taken by Ansel Adams that are portrayed above. The actual images of Japanese Americans show a regular person, not much different than any other US citizen, while the images of propaganda capitalize on the idea of the “other.”

“Fourteen heroic Japanese-American Boy Scouts defied a mob of pro-Axis sympathizers attempting to seize the American flag during a fatal riot at the Manzanar Relocation Center last Sunday.” (Merritt 1942, 1)

The quote above was taken from an article in the Christian Science Monitor in December of 1942. Contrary to the popular belief in the United States at the time, not all Japanese Americans identified with the “other.” The boys display of protest against the riot shows the difficulties of putting one group of people into the same box. Boy Scouts are in some ways symbolic of the all-American, they embody everything being an American is known for… from patriotism, to being well versed in the outdoors, and everything in between. It is hard to even imagine the juxtaposition of identity that Japanese Americans must have felt during the internment period. Many Japanese Americans had embraced US culture and identity while still holding on to parts of their Japanese heritage. “Widespread bitterness and hatred in the United States towards the Japanese also made the Japanese American question the Japanese side of their identity.” (Luther 2003, 70) The hateful messages and anti-Japanese sentiment that was spread by both the government and the media must have been entirely overwhelming for a group of people who were already fighting to prove their innocence and obedience. Even when Japanese Americans attempted to shed any semblance of their Japanese identity they were still met with racial impartiality, on the basis that they looked more Japanese than American. There was this expectation for those restricted to internment camps to carry on with their lives within the boundaries of the camp, but at the same time everything they knew had been uprooted and they were surrounded by barbed wire and men with guns.

“This Japanese relocation center has been transformed within four months from the “problem child” of the war relocation authority into a model camp with less major crime and fewer misdemeanors than any city of comparative size in the country.” (Gentry 1943)

This excerpt was taken from a 1943 article in the Chicago Daily Tribune. The context of the excerpt provides an interesting perspective on the relocation centers in comparison to United States towns. The article addresses crime in Manzanar relocation center and how it has less major crime than any city in the US of a similar size, this would have been a surprising revelation in 1943 as anti-Japanese sentiment was still hanging around in the form of propaganda and media sensationalization.

The internment of Japanese-Americans during WWII is a dark moment in history for the United States government. US citizens, many born into a life in the United States, were forced from their homes and jobs and made to live like animals for an extended period of time. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941 was the spark that ignited an anti-Japanese sentiment within the United States. The US government used the attack to promote anti-Japanese propaganda that promoted fear, distrust, and paranoia among American citizens. Had the attack not occurred it is likely the government would not have had the momentum needed to intern Japanese Americans living on the West Coast in the manner that they did. Japanese Americans were made to question their identity and were constantly plagued with sentiments that portrayed them as rats and savage. The idea of the “other” was placed upon Japanese Americans… no matter how ingrained in US culture they were. The ramifications of the internment can still be seen today through generations who witnessed the atrocities in real time, or those who felt the pain through their elder’s detail of their experiences. The actions of governments and media during wartime have lasting consequences and it would be beneficial to thoroughly examine the possibilities of such decisions without a wartime bias.

Bibliography

Primary Source:

- Adams, Ansel. “Tojo Miatake Family.” Photograph. Manzanar Relocation Center. From Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

- Adams, Ansel. “Catholic Church.” Photograph. Manzanar Relocation Center. From Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

- Adams Ansel. “Co-op Store.” Photograph. Manzanar Relocation Center. From Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

- Brink, Rodney. 1942. “Internment Of Japanese Is Demanded.” The Christian Science Monitor.

- Gentry, Guy. 1943. “Japs’ Evacuee Camp a Model for U.S. Towns: Firmness and Fairness End Unruliness.” Chicago Daily Tribune.

- Hotchkiss. 1944. “Your Enemy the Jap.” Photograph. US Government Printing Office. https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/28722/bk0007s8c5k/

- Merritt, Ralph. 1942. “Japanese Boy Scouts Save Flag from Mob at Relocation Center.” The Christian Science Monitor.

- “Don’t Blab.” United States Propaganda. Photograph. Origin Unknown.

- “Open Trap…” United States Propaganda. Photograph. Origin Unknown.

Secondary Source:

- Bram, Steven. 2004. Game Theory and Politics. Dover Publications, New York. xv.

- Fickle, Tara. 2014. “No-No Boy’s Dilemma: Game Theory and Japanese American Internment Literature.” Modern Fiction Studies. Baltimore. 60:4. 740-761.

- Luther, Catherine. 2003. “Reflections of Cultural Identities in Conflict: Japanese American Internment Camp Newspapers During WWII.” Journalism History. 29:2. 70.

- Saavedra, Martin. 2015. “School Quality and educational attainment: Japanese American internment as a natural experiment.” Science Direct: Explorations in Economic History. 57. 59-78.

Tertiary

- Takei, George. “Internment, America’s Great Mistake.” The New York Times Opinion. 28 April, 2017.